Insurance Curious

by Angus MacCaull

In 2018 I traveled from my small town in Nova Scotia to a major US city. The Canadian subsidiary of a US insurance giant paid for the trip, which included an expensive steak dinner and a tour of an innovation hub. My job was to identify emerging trends that would be worth our time and attention at AA Munro. How should we use technology to help Maritimers manage risk so they can drive their cars, protect their homes, and grow their businesses?

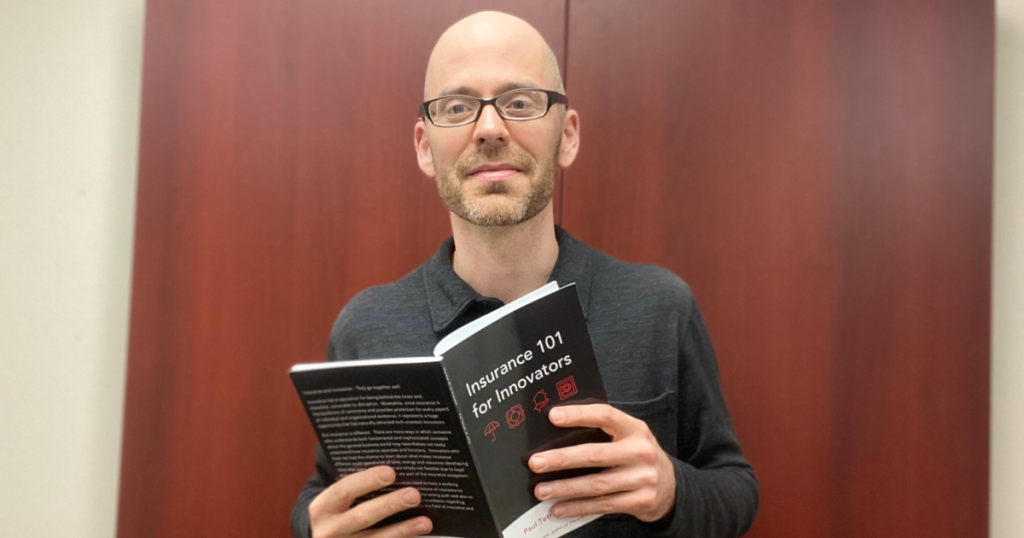

A lot of people are interested in using technology to improve our industry. Some of them, like me, are familiar with the quirks of the products we sell: promises made up of particular arrangements of words—wordings we call them—backed by a complicated regulatory framework and complex legal precedents. But many entering insurance now come from a background in software or investing. They don’t really know how insurance works. They see a lot of money changing hands each year and figure they can add enough value to earn some of it for themselves. In Insurance 101 for Innovators, a new book by executive director of The Insurance Library Paul Tetrault, these these new entrants are coined “insurance curious.”

On the night of that steak dinner south of the border, I met with a couple of people beforehand for drinks. One was our host, a senior leader at a carrier. The other was the owner of a large brokerage in acquisition mode in Central Canada. At one point in the conversation, I was identified as a bleeding heart liberal by the latter—shortly after I pointed out to the former that highways are political. Where a highway goes and stops both reflects and determines aspects of the value of the communities that can or can’t use it. Big government infrastructure decisions aren’t neutral. This is something my grandfather, AA Munro himself, understood well when he advocated for the Trans-Canada Highway to run on the north side of the Bras d’Or Lake through his own hometown rather than the south. Was north the best side for the most number of people? I don’t know. It is the side I still prefer to drive on today, even after the development of the other.

Well before the insurance curious entered the scene, before Web 2.0 and even before the dot com bust, the Internet was called an information superhighway. These days it’s called a cloud. I think it’s more like an ocean—with its depth, murkiness, and monsters within—but for the purpose of understanding what’s playing out now in our industry, the idea of a digital highway is useful. My notion of an ocean is perhaps too poetic; and talk of the cloud is misleading—as if the ongoing creation of the Internet is natural and vaguely placeless rather than the direct result of specific people building servers in Menlo Park or Dublin.

“Contrary to popular perception, the insurance industry has historically been an early adopter of technology,” writes Rob Galbraith in the forward to Tetrault’s new book. As anyone familiar with insurance knows, we already have digital highways. They’re just old. They need resurfacing at a minimum. Maybe some of them should be rebuilt on the south side of the lake. And with infrastructure projects this large, you know the government needs to be involved.

“Insurance companies exist ultimately to do one thing: pay covered claims,” writes Tetrault. Most of all that money changing hands each year goes to claims. People argue that claim frequency and severity could be cut down; or distribution expenses; or fraud. These are some of the areas the insurance curious are working on. In some ways I’m like them, a would-be innovator with a background outside the industry. I don’t come from the worlds of tech or finance. And though I grew up in an insurance family, I’m ultimately a writer. Once I identify trends through research, I’m wired to think deeply and tell stories.

After the steak we went for drinks again. The final member of our tour arrived late from Western Canada. We clinked our glasses of beer and Scotch and I don’t remember what else. Side conversations started. Million premium this. API that. Data. Sales. Culture—each of us planning growth in the ways we understood best.

Leave a Reply